Can New Space Firms Plug Europe’s Gap in Defense Tech?

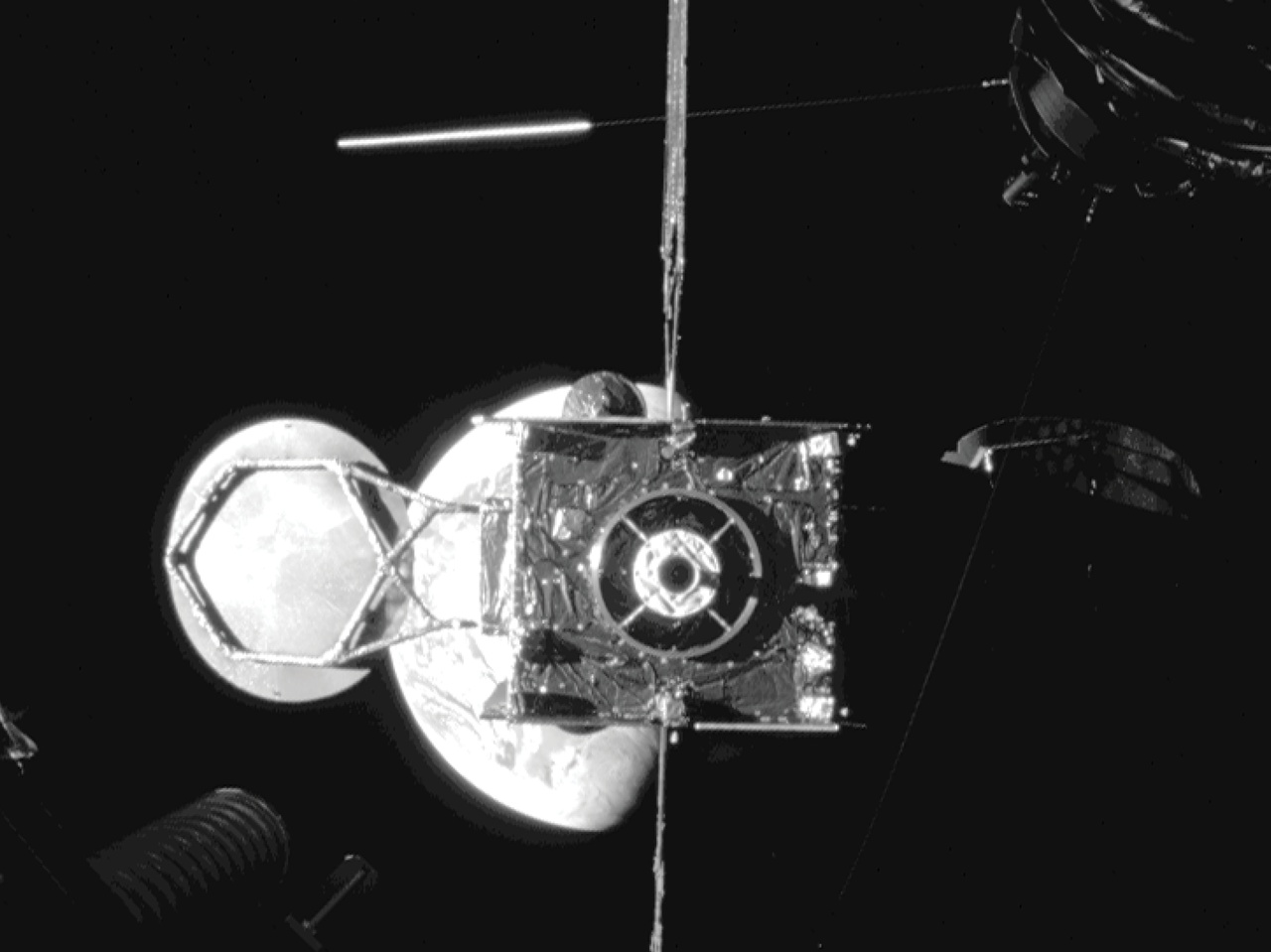

Europe is racing to fill a gap in defense and space capabilities. Space startups have seen a spike in demand and say they are ready to fill the gap, while calling for Europe to rethink its procurement mechanisms and preference for traditional primes. August 25th, 2025It’s been a busy time for Finland-headquartered Iceye. The 11-year-old satellite Earth-Observation (EO) company, an undisputed unicorn among European new space firms, has over the past few months been releasing back-to-back contract announcements. A host of European nations have ordered synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites including the Polish Armed Forces, the Portuguese Air Force, Finland, and the Netherlands. On top of that, there is a deal to provide data to the NATO Allied Command Operations and plans to build new satellite factories in Germany, Greece, and Portugal.

This harvest of contracts, Iceye’s Vice President for Missions Joost Elstak admits, is a result of Europe’s awakening to its geopolitical vulnerabilities and the increasing need to strengthen its own space infrastructure in response to current international relations.

“We are getting a lot of contracts right now from various Ministries of Defense,” Elstak told Via Satellite. “That’s obviously driven by the geopolitical situation but at the same time, the new space industry has matured over the past 10 years, and we are at the level that we can actually supply these services.”

Iceye currently operates 54 SAR satellites — the largest commercial SAR constellation in the world. Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Iceye has positioned itself as a strategic player, providing a steady stream of data to Ukraine and even dedicated access to one of its satellites that was bought by the Ukrainians following a crowd-funding campaign in 2022.

Stepping Up

Europe’s EO sovereignty was cast into stark light in March when the U.S. administration temporarily stopped sharing intelligence data with Ukraine following the public bust-up between Presidents Trump and Zelensky. That pause affected Ukraine’s access to satellite imagery from U.S. governmental as well as commercial satellites including those from Maxar, Planet, and BlackSky.

Although the U.S. turned the data tap back on after only a week, Europe could no longer remain in denial — it didn’t have the technology to make up for the unavailability of American satellite imagery. While Iceye could supply SAR data with the near real-time frequency required to monitor a fast-evolving battlefield, there was no one in Europe to cover the shortage in the high-resolution optical spectrum. Airbus, which operates the two high-resolution optical Pleiades Neo satellites, didn’t want to comment on the matter.

The lack of fully fledged commercial constellations is only one part of Europe’s problem. Pierre Lionnet, a space industry analyst and managing director at the European space industry’s trade association Eurospace, estimates that European armed forces combined possess 10 times fewer spy satellites than the U.S. government.

Similarly, Starlink — indispensable for the Ukrainian forces since the early days of the war — is currently irreplaceable. Access to the constellation’s services was reportedly used as a bargaining chip in negotiations surrounding the notorious minerals deal between the U.S. and Ukraine. Ukrainians rely on Starlink not just for civilian connectivity and to keep troops online while on the move. They mount Starlink terminals on drones to increase their range and hit targets deeper in the enemy-controlled territory.

The OneWeb constellation, Europe’s sole up-and-running Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) broadband system, is also deployed in Ukraine to support government and institutional communications, contributing to a recent spike in government services revenue. Leadership recently said a new manpack terminal for military use is in the works.

Yet OneWeb offers only about one-twentieth of the capacity provided by SpaceX’s Starlink, according to Clayton Swope, an aerospace security analyst and deputy director at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies. OneWeb’s terminals also are not lightweight enough for use on drones. Eutelsat OneWeb chief communications officer Joanna Darlington told Via Satellite that the company has sold all the capacity available in Ukraine, but has no plans to significantly change the way it does business to bring its offering closer to that of Starlink.

“We are and will remain a company that is offering services to business, institutional customers, and governments,” said Darlington. “The Starlink constellation has a lot more capacity because it wants to address consumers directly, which is clearly what we don’t want to do.”

The OneWeb constellation currently offers 1.1 terabits of capacity. Its second generation, which will form a part of the European Union’s IRIS² constellation, according to Darlington, will increase that capacity to 1.5 terabits. That, however, will only be available in the next four to eight years, Darlington added.

For Ukraine, that means no chance of switching their attack drones to another satcom provider any time soon.

Europe Waking Up

It’s not just about Ukraine. Russia’s dictator Vladimir Putin makes no secret of his imperialist dreams and other nations along Russia’s western border fear a future invasion.

“Europe has finally realized that we have this huge capability gap, and the question now is how do we catch up,” Satellite & Telecoms Consultant Christian von der Ropp told Via Satellite.

According to Lina Pohl, a research fellow at the European Space Policy Institute (ESPI), European new space companies raised 1.5 billion euros ($1.75 billion) in investment in 2024, the largest single year increase since 2014. Out of the funded companies, 40 percent have explicit links to security.

The EU banks on the IRIS² multi-orbit secure communications constellation to decrease its reliance on Starlink. But IRIS², formally approved after years of discussions in 2024, will not be operational before 2030. On the intelligence side of things, the European Space Agency (ESA) is seeking 1 billion euros ($1.2 billion) to develop a military grade EO network, but that too is years away from completion.

The IRIS² project, in particular, has drawn criticism from some quarters for providing too little too late. The constellation will consist of 290 satellites and will be built by a consortium of European aerospace primes including Airbus and Thales Alenia Space and operated by Eutelsat, SES, and Spanish operator Hispasat.

“IRIS² is already outdated today in terms of capacity and capabilities,” says von der Ropp, who is critical of the project’s set-up. “Forcing the entire European space industry into a single big consortium is just creating conflicts of interest, moral hazard and inefficiencies, some of which are already visible today,” he adds.

For many, IRIS² is a textbook example of the clumsiness of large European space programs, Europe’s preference for old-school primes and micro-management of its space projects — an attitude some consider unsustainable amid the imminent threat of Russia.

“They have a tendency to create these mammoth projects where they dictate everything, they set requirements and allow absolutely no room for iterative design and innovation,” says von der Ropp.

Raycho Raychev, founder and CEO of Bulgaria-headquartered smallsat manufacturer EnduroSat, shares those views. “The European agencies are biased towards a few very big players,” he says. “The tenders typically almost exactly describe the technical solution offered by a certain company instead of describing the challenge and choosing a winner who is best able to solve it.”

This attitude, Raychev believes, has for years prevented ambitious new space players from winning substantial contracts and scaling fast. But first hints of Europe’s willingness to rethink their approach may already be visible, he says, as the pressing security needs call for more dynamic and responsive solutions.

Nations Moving Fast

In the meantime, national governments, concerned about strategic sovereignty and not bound by the complex politics that hinder the EU and ESA, are ready to purchase their own assets from the likes of Iceye, possibly with the view of combining them with those of trusted partners for improved coverage.

“In the past, it was only big countries like France or Germany who could afford to have their own satellites,” says Iceye’s Elstak. “These missions would consist of two or three satellites and cost about a billion euros. But with the type of technology that we offer and the capabilities that we can squeeze out of our small satellites, we can now offer a performance that is even better than that of those old systems and do it at a cost that is an order of magnitude lower.”

Lionnet agrees that the current spike in national defense funding plays into the cards of those new space players who have managed to create a track-record of flight proven technologies in the previous years. He also thinks that companies with links to major western European nations with substantial budget contributions to ESA are best positioned to benefit from the current defense spending spree as local MoDs are likely going to favor domestic offerings where such are available.

Underdogs Rising

Other players also report increased demand from the geopolitical situation. Atle Wøllo, CEO of Lithuania-based Kongsberg NanoAvionics, tells Via Satellite that the company is seeing “the biggest order intake in its history right now, and a lot of interest” in their products, although he would not disclose more specifics.

“We are winning more contracts than we have ever done, and we see that the political situation, both in terms of the war in Ukraine but also the situation in the U.S. generates an increased need,” Wøllo says. “The current U.S. administration is forcing Europe to stand up and commit to increased spending, which for us means a growth opportunity, because we are in a position now where we can make a difference.”

NanoAvionics, a spin-off from the University of Vilnius founded in 2014, was acquired in 2022 by Norwegian technology group Kongsberg. The company manufactures small satellites up to the mass of several hundred kilograms and has launched over 50 spacecraft for various customers since its conception.

“We see now that [procurement] decisions in Europe are happening faster,” Trond Hegrestad, vice president SmallSat Systems at Kongsberg Defence & Aerospace, tells Via Satellite. “We don’t have time anymore to follow the old-fashioned way.”

In April, NanoAvionics signed a contract with SpinLaunch to build 280 satellites for the American firm’s LEO broadband constellation Meridian. SpinLaunch’s ambition is to ultimately deploy a fleet of up to 12,000 satellites, positioning the firm as a possible competitor to Starlink. It is, however, not clear how much of the needed funding SpinLaunch has already raised.

Wøllo says that NanoAvionics plans to build a manufacturing plant to fulfil the contract directly in Lithuania, rather than relocating facilities to the U.S. He hopes the venture could provide Europe with a new LEO broadband solution — a player more agile than the EU-sanctioned IRIS² and Eutelsat-owned OneWeb.

“This is something we believe we can bring to Europe quite fast and fill a gap,” Hegrestad says.

Companies like NanoAvionics and EnduroSat are a rare breed of European new space companies that have emerged as significant players in the field while not hailing from large western European states with significant budget contributions to ESA.

Bulgaria is not an ESA member state at all, while tiny Lithuania only gained an associate member status in 2021. Both nations, however, have decades of experience with Russian oppression, which makes them particularly invested in the European defense situation. Norway, the home of NanoAvionics’ parent Kongsberg, too has a border with Russia, and so does Iceye’s home nation Finland.

“We are old enough to remember how hard it was in the old Communist times,” says Raychev, who founded EnduroSat in 2015 as a spin off from a technology leadership program he founded five years earlier. Since then, the company has launched over 60 missions and set up offices in five European countries and the U.S.

Raychev attributes Endurosat’s success to the mindset strengthened through that past adversity, which is not unlike the determination of Ukrainian defense tech innovators developing cutting-edge drones at rocket speed to keep Russian troops at bay. He is confident his firm will secure its spot in the European defense race based solely on its merits, just like Ukrainian drone innovators.

That is, if Europe chooses to learn from the Ukrainian defense tech boom and allows innovative solutions to spring up without restrictions under the geopolitical pressure.

“Ukrainians have demonstrated what is possible when you have a very huge pressure and a very open way of innovating,” Raychev says. “There are no boundaries [in Ukraine] on how much you can innovate and no administrators defining what the solution should be to a particular problem.”

Iceye’s Elstak says the company’s experience supplying intelligence to Ukraine’s forces has been a major innovation driver, especially in data dissemination and analysis, which is now proving a boon for the new European defense customers.

“It has really been a catalyst for us,” Elstak says. “The feedback loops we have with the Ukrainian users are really short and it’s really helping us develop appropriate products, which connect really well with the user needs we have at the moment in Europe.” VS