A Closer Look at VLEO: The New Frontier in Orbit

December 2nd, 2025As the fast-evolving commercial satellite sector looks to leverage the advantages of Very Low Earth Orbit (VLEO), situated at the edge of space in orbits between 250 and 400 kilometers above the Earth’s surface, several satellite firms see it as transformative for commercial and defense space applications.

“VLEO is incredibly exciting because it’s a new frontier,” says Chad Fish, vice president of strategy and CTO of Orion Space Solutions, a subsidiary of Arcfield.

The benefits of being closer to Earth are clear: sharper imagery, better signal quality, precise positioning, reduced latency, efficient spectrum use, and a "self-cleaning" orbit where debris naturally decays.

According to Tom Campbell, president of Redwire Space Missions, VLEO’s proximity to Earth enhances perception dramatically, depending on the type of signal.

“An RF signal strength drops off quickly with distance, but VLEO gets satellites half as close to the ground, making a sensor four times more perceptive,” he explains.

The effect is even greater for radar payloads, where radio frequency (RF) energy is beamed to the ground and then bounces back, which translates to an eight-time increase in perception. The orbit also makes constellation architectures more resilient, with the ability to not only look down at the ground but also to look up to track debris or support missile defense.

However, these benefits come with challenges: VLEO, which begins at the Kármán line, requires constant propulsion or re-boosting to maintain its altitude. And VLEO’s location in the upper atmosphere means it’s surrounded by atomic oxygen. In contrast to O2, which is essential for life, atomic oxygen is short-lived and quickly reacts with almost everything. It causes significant aerodynamic drag, leading to rapid orbital decay for satellites and systems.

Despite these drawbacks, VLEO was used for U.S. spy satellite missions beginning in the 1960s. Spy planes flying in VLEO captured high-resolution surveillance images, which were dropped in specialized reentry canisters equipped with a heat shield.

Now, thanks to promising advances in propulsion technology and material science, there’s renewed interest in VLEO.

“The market potential for VLEO is substantial, with interest in investment from both commercial and defense sectors worldwide,” says Alex Webb, senior research analyst with Juniper Research’s Telecoms & Connectivity team.

Juniper Research makes the bold projection that global investment in VLEO will grow to $220 billion by 2027, representing a 1,100% increase over three years. By 2030, the number of operational satellites in VLEO is expected to exceed 620, a dramatic rise from the handful of planned assets in 2025.

And the U.S. isn’t the only country focused on the lowest orbit to Earth: China is heavily investing in VLEO technology for both commercial and military applications, according to the U.S. Space Force’s Space Threat Fact Sheet. China Aerospace Science and Industry Corp (CASIC) is planning to have a cluster of 192 satellites by 2027 and 300 by 2030, operating at altitudes of 150 to 300 kilometers from Earth.

Several space players are racing to deploy new technology and platforms for VLEO. The shorter distance to the ground enables ultra-low latency communication and faster data transfer rates, providing near-real-time intelligence to ground users, a key requirement for modern military operations as well as for telecommunications, disaster response, and environmental monitoring.

Research Breakthroughs in Propulsion, Materials

Driving rising interest in VLEO are advances in air-breathing electrical propulsion systems as well as breakthroughs in material science.

“The biggest challenge of orbiting in VLEO is staying in VLEO,” notes Sven Bilén, Penn State professor of engineering design, of electrical engineering and of aerospace engineering. He is also principal investigator of a $1 million study with the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Defense Sciences Office as part of its Charge Harmony Disruption Opportunity.

The program calls for orbits that are "technically defined as below VLEO, or sometimes what we call sub-Karman line orbits” — roughly 100 kilometers or 60 miles from the ground, he explains.

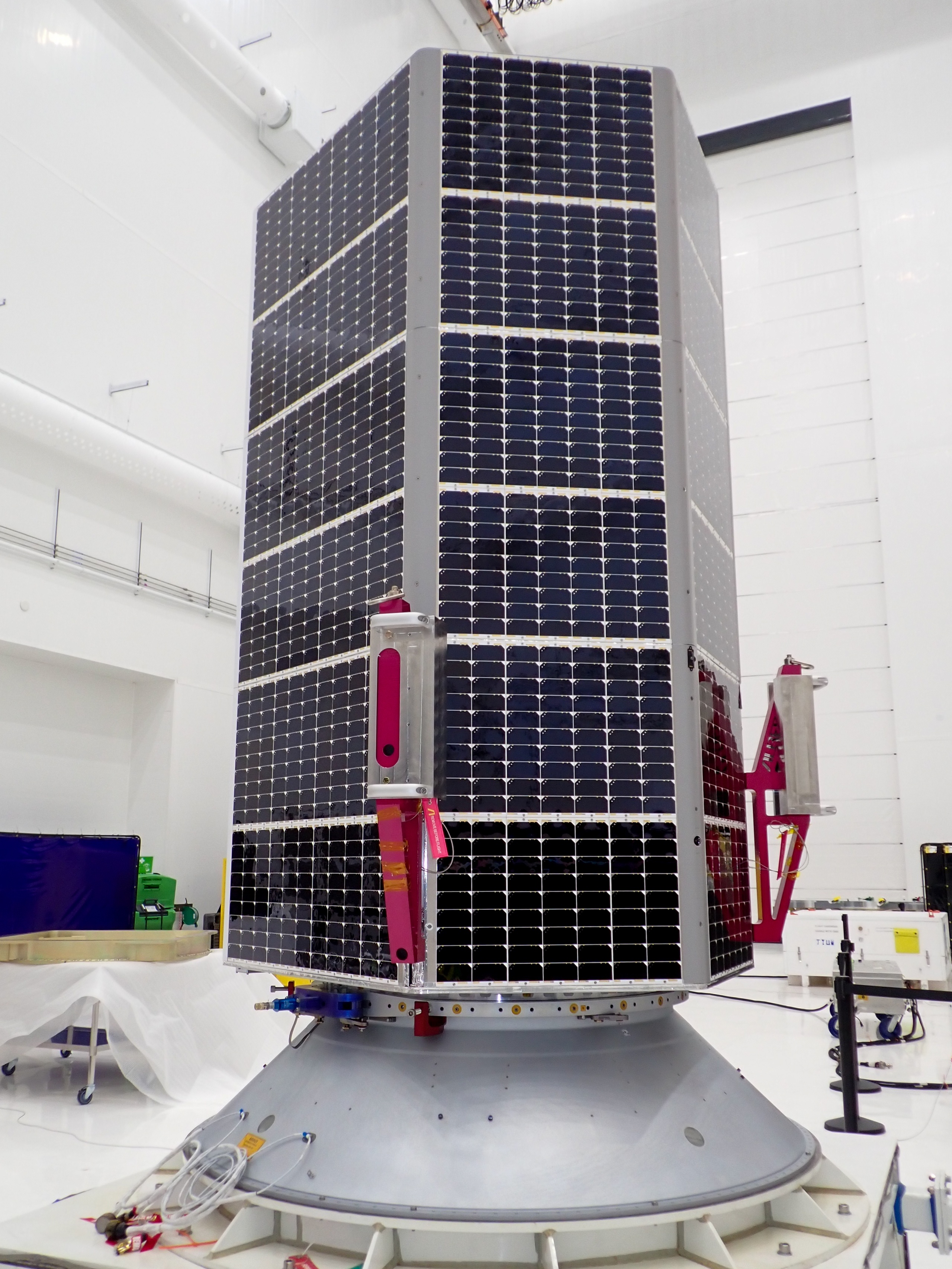

“How do you get the energy you need on board to run the system? What you typically see with VLEO spacecraft is they’re covered in solar cells. You’re collecting more electrical power, but you’re also creating a lot more drag,” Bilén adds.

Penn State and its research partner, Georgia Institute of Technology, are in their second year, developing a novel air-breathing microwave plasma thruster to help VLEO spacecraft stay in orbit.

Co-principal investigator Mitchell Walker, William R.T. Oakes Jr. School Chair, Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering at Georgia Tech, notes that propellant requirements vary depending on changes to day-night cycles, seasons and solar activity. As a result, “VLEO demands high flexibility and adaptability in propulsion devices, far beyond conventional systems.”

Walker explains that a major technical challenge is designing systems where the propellant, mostly atmospheric oxygen at VLEO, goes out at a higher velocity than it enters — a process similar to what occurs in jet engines rather than traditional space propulsion.

Bilén says the research is at the lab-demonstration stage, “but there’s a lot of work to get that to a flight-ready prototype.”

Walker expects that a flyable system will launch in the near future. “The question is, what will the performance be and how long will it last?”

Timothy Minton, aerospace engineering sciences professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, is tackling another VLEO problem: the corrosive effect of atomic oxygen atmosphere on satellite systems. His team is developing new material systems that not only resist atomic oxygen’s harsh effects, but also minimize aerodynamic drag, a dual goal key to extending satellite lifespans in VLEO and reducing fuel consumption.

Minton’s team has pioneered the use of advanced polymers coated with ultra-smooth, atomic oxygen-resistant layers such as aluminum oxide and zirconium oxide applied through atomic layer deposition. The coatings protect and prolong the life of satellite surfaces.

“Having both resistance to atomic oxygen and low drag is essential if we’re to increase the lifetime of satellites in VLEO,” says Minton, whose research focus also involves using molecular beam-surface scattering data as a basis to develop gas-surface models to predict drag.

An Answer to LEO Crowding?

If these and other research breakthroughs make VLEO viable for longer-duration missions, it could provide an alternative to an increasingly crowded LEO environment. As many as 70,000 satellites are expected to launch into LEO over the next five years, the majority from China.

“The crowded nature of LEO is definitely a concern for satellite providers, but the advantages you get for both observation and communications are definitely other big appeals [of VLEO],” says Webb.

As a self-cleaning orbit, VLEO offers a compelling answer to the orbital crowding facing LEO. Fish contends that “whatever you can do in LEO, you can do in VLEO – only better. You get sharper measurements, more precise data and new vantage points that haven’t existed before.”

Orion Space is participating in DARPA’s Guest Investigator Program to advance understanding of the VLEO region. It is preparing to deploy DARPA’s Ouija nanosatellite, designed for long-duration operations in VLEO. Originally set to launch in June, the mission will carry a suite of ionospheric and high-frequency sensors and instruments to help classify VLEO, giving DARPA novel insights into the HF environment to inform future national security and communications initiatives.

Commercial Players Embrace VLEO

Another VLEO company, Albedo, based in Colorado, recently pivoted to focus exclusively on building platforms for the VLEO market, rather than selling commercial imagery collected from VLEO.

“We’re going all in on VLEO,” says Topher Haddad, co-founder and CEO.

The company plans to market its VLEO satellites and buses to other operators, though its current customers are government agencies like the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and the Air Force Research Lab (AFRL) looking to capitalize on data available from Albedo’s Clarity-1 VLEO satellite, which launched in March. Clarity-1 is designed to orbit below 300 kilometers from Earth and serves as an alternative to planes or drones in denied areas and conflict zones.

NRO is buying visible and thermal IR data from Albedo’s satellite as part of the NRO’s Strategic Commercial Enhancements program. The AFRL awarded Albedo up to $12 million last March to share its VLEO on-orbit data to support the Lab’s new mission and payload development efforts.

According to Haddad, VLEO’s proximity to Earth unlocks new scalability and performance for next-generation satellite systems.

"VLEO unlocks a holy grail triple combo for several mission sets,” Haddad says. “Being that close enables exquisite capability but not at an exquisite price. You then spend those savings on proliferation. And because of the drag and being beneath the belts that trap radiation, you're diversified from bad days in LEO. Exquisite, proliferated, and diversified."

Addressing drag keeps satellites in orbit longer. Albedo says the materials and coatings used on Albedo VLEO hardware minimize atomic oxygen damage, enabling it to achieve a four-year mission life. The company is now focused on manufacturing at scale.

Haddad says being vertically integrated will accelerate his company’s speed to market: “The more we have in-house, the faster we can go and the more we can scale the volume.”

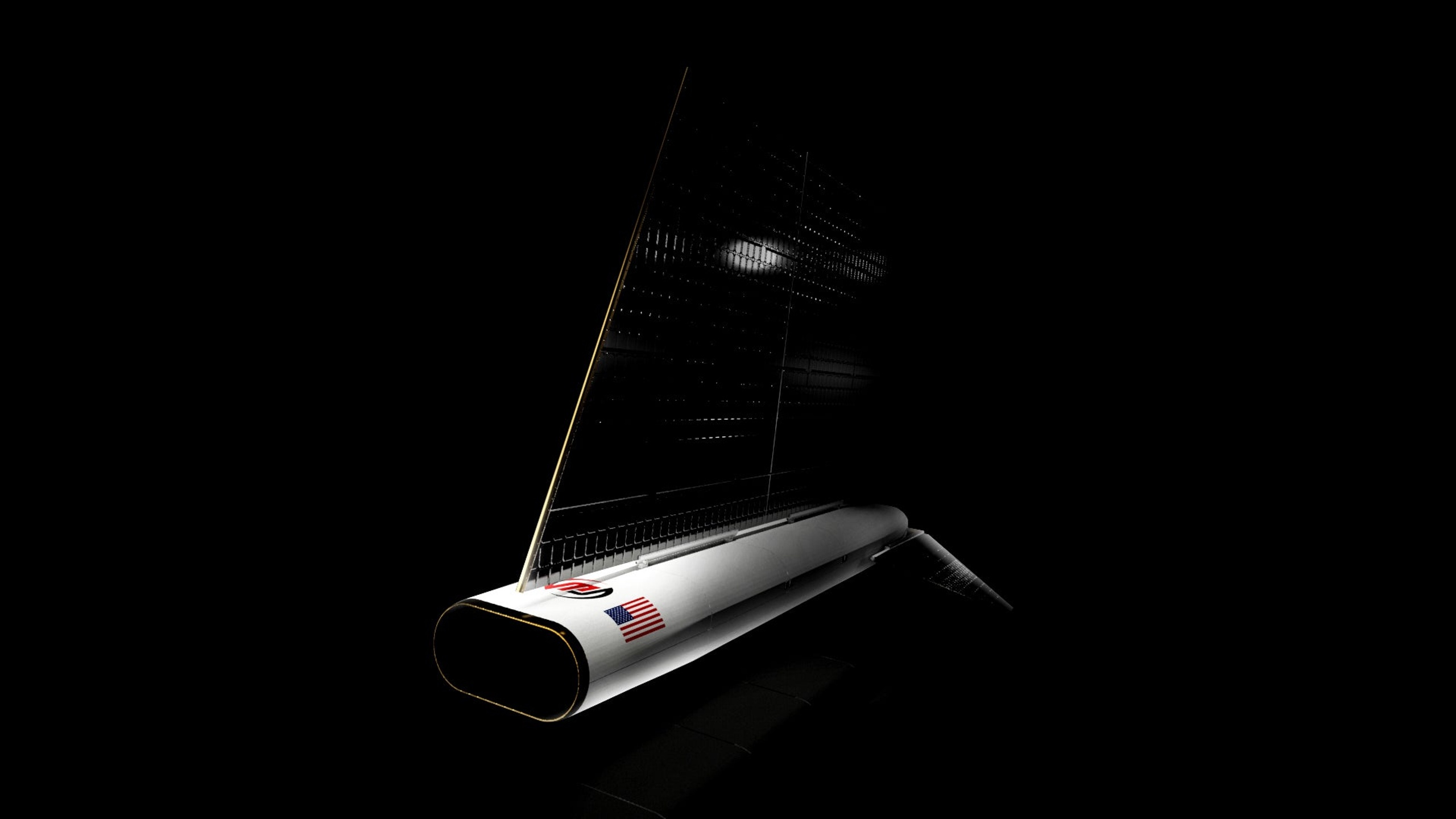

Another VLEO player, Florida-based Redwire Space, has developed two VLEO platforms – SabreSat for the U.S. market and Phantom for Europe.

The company recently announced its second DARPA award, valued at $44 million, to finish building an air-breathing spacecraft for the agency’s Otter’s VLEO mission. Under the phase 2 contract, Redwire will manufacture and deliver its SabreSat platform for the mission, which DARPA hopes to use to demonstrate that long-duration flights of more than a year in VLEO are possible.

Campbell frames Otter as a revolutionary air-breathing satellite that will demonstrate the use of novel electric propulsion systems in VLEO. Air-breathing systems use air around the satellite or spacecraft and repurpose it as fuel.

Phantom, Redwire’s VLEO platform for the European market, was developed to operate for up to five years in orbit and was selected for Skimsat, the European Space Agency’s small-satellite demonstration mission in VLEO.

“Having a European and U.S.-sponsored development program for persistent VLEO puts us in a good position to serve the warfighter,” says Campbell, noting that defense is driving most VLEO investment, with some commercial investment for high-resolution imagery.

Redwire depends on its digital engineering tools to model space weather effects in VLEO and to simulate atmospheric drag and material degradation from atomic oxygen.

“Digital engineering is central to Redwire’s strategy for VLEO mission and constellation development,” says Campbell. “Ultimately, it will let us iterate quickly, validate design decisions, and tailor VLEO constellations to meet exact customer requirements—ensuring mission success and efficient use of space assets.”

Another Florida-based company, Star Catcher, is working to build what could be the first power grid in space and envisions its network being a game-changer for VLEO.

“When you couple power beaming with electric propulsion, it actually lets you stretch your fuel further,” explains Andrew Rush, co-founder and CEO of Star Catcher. He uses the analogy of a car getting more gas to that of adding more power on the satellite, explaining that power combined with new types of electric propulsion thrusters can “increase the gas mileage on the spacecraft.”

“We anticipate Star Catcher will enable VLEO satellites to generate 2 to 10 times more power without needing larger solar panels,” he says.

Star Catcher began operations 15 months ago. It has held several technical demonstrations and announced an agreement with Astro Digital, a space-as-a-service manufacturer, to buy power from Star Catcher’s grid to fuel its satellites. Rush says its power grid should come online in time for the first VLEO launches, with it benefiting from advances in air-breathing electric propulsion from firms like California-based Viridian.

“When you combine the power source with air-breathing technologies such as what Viridian is developing, those together create true aircraft-like operations and performance envelopes in LEO,” Rush says.

“Air-breathing electric propulsion will fundamentally change how we fly satellites by enabling these vehicles to sustain their operations lower and longer than ever before, even using the collected atmospheric propellant to maneuver on demand,” commented Viridian co-founder and CTO Matthew Feldman. “Technologies like Star Catcher's solar beaming will super-charge systems like our air-breathing electric propulsion system to enable even greater mission sets.”

Viridian was recently awarded two Phase II Small Business Innovation Research awards for its Air-scooping Electric Thruster Technology, or ASET. The system collects air from the upper atmosphere for fuel, creating a refuelable satellite platform.

“Viridian has already validated key components in ground-based testing and is using these recent awards to accelerate towards an integrated propulsion system capable of sustaining flight in VLEO indefinitely,” he says.

An Optimistic Outlook

But VLEO’s value goes beyond defense applications, says Webb. The Juniper Research analyst sees a powerful use case for VLEO in direct-to-device (D2D) and direct-to-satellite communications, where smartphones and IoT devices can connect directly with satellites. The potential addressable market is massive, considering that there are almost 10 billion mobile subscribers and 4 billion cellular IoT devices globally. “Successful adoption depends on business models and end-user pricing,” Webb says.

SpaceX is targeting VLEO for its Direct-to-Cell constellation, recently filing for a new constellation that includes satellites in VLEO and LEO.

Other commercial use cases include Earth Observation like high-resolution imagery, environmental monitoring, and asset tracking.

Looking ahead, industry leaders envision a future where VLEO will become as proliferated as LEO.

“It’s very possible that in the next decade we will see the same kind of proliferated constellations that are emerging in LEO exist in VLEO,” says Star Catcher’s Rush.

“We’ll see thousands of satellites in VLEO. And because it’s self-cleaning, debris only lasts a few weeks — making it a truly sustainable orbit,” adds Haddad with Albedo.

Redwire expects airborne and space assets will one day work together in VLEO, which becomes particularly relevant for mission planners for Golden Dome, the U.S.’s proposed multi-layer missile defense system designed to detect and destroy ballistic, hypersonic, and cruise missiles before they launch or during their flight.

“We believe that the fight will be won via multi-domain and that blurring the lines between airborne and space is a necessity,” says Campbell, who envisions airborne and VLEO drones working together, with operators optimizing which platform to use based on the sensing and the effects they need to deliver.

“VLEO enables much finer ground sampling for sensing applications, while airborne platforms can complement or extend capabilities close to the Earth’s surface,” Campbell explains.

Combining VLEO satellites with airborne platforms will give national security mission operators “multiple options to quickly detect, track or respond to dynamic threats,” concludes the Redwire executive. VS