Ground Station Operators Look to Software for Simplicity in Smallsat Operations

Outsourcing the ground segment may be cheaper and easier for smallsat operators than building their own network of ground stations, but it is still a complicated and difficult process. A new generation of Ground-Station-as-a-Service providers aim to insulate operators from that complexity, and feed the growing hunger for space-based connectivity. July 28th, 2025In today’s brave new space world, smallsat companies can outsource everything. Launch is a given, and even satellite buses can now be bought off the shelf or rented as part of a space-infrastructure-as-a-service offering.

The ground can be outsourced, but as with cloud computing, the simplicity and low cost promised by ground outsourcing doesn’t always materialize, smallsat operators say. Even with a third-party provider, wrangling the ground segment remains difficult and complex. Abstracting that complexity away from the customer remains the holy grail for ground-station-as-a-service startups as they scale to meet the burgeoning demand from new space companies.

To maximize their bang for the buck, smallsat operators need to be “expert customers," and exercise caveat emptor (Latin for buyer beware), according to Stephane Germain, founder and president of GHGSat.

The company, which has a Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) constellation of 13 satellites monitoring emissions of greenhouse gasses like methane and launched its first satellite in 2016, is one of the earliest Earth Observation (EO) constellations of the “new space” age, says Germain.

“We always knew that our sweet spot would be tens of satellites, not hundreds or thousands, so it would make sense to outsource everything we can,” he says.

GHGSat’s experience reflects the choices faced by many smallsat companies as they seek to control costs and scale their constellations. Other operators have chosen to insource the ground, establishing their own network of ground stations, even building their own antennas, but Germain says he rejected that approach.

When it comes to the ground segment, GHGSat takes a couple of approaches. The company maintains two ground station suppliers—KSAT and C-Core—and that’s on purpose. “Ultimately, it's good business to have more than one supplier that you can flex to at any given time,” Germain says.

The company sees its suppliers as partners. “We're not just going to drop somebody overnight because of a hiccup. But we do believe that there should be performance objectives and that there should be rewards for performance and penalties for non-performance.”

“It's an incentive thing,” Germain says.

Customer-Driven, Constantly Shifting

With its two ground station suppliers, GHGSat uses a wide range of payment/leasing models that range from time-sharing on an antenna, paying for a dedicated antenna, and buying reserved time slots on an antenna. “We do all of that. That diverse mix, that’s deliberate.”

That range of arrangements enables flexibility, both operationally and cost-wise, Germain says. “We can live with latency on some of our data, but with other parts of our data we need near real-time. Having that mix [of ground station arrangements] we can flex between different models depending on the capacity we need, supplementing our dedicated antennas through a pay-as- you-go type of arrangement when we need surge capacity.”

“It’s a constantly moving mix,” he says.

Paradoxically, Germain explains, the company’s success at outsourcing relies on the total mission ownership approach it adopted in its early days, when it controlled the entire system end-to-end.

GHGSat staff managed the whole process in those early days. “We owned the satellites. We operated the satellites. We were responsible for the scheduling of the downlinks, for booking the antennas. … We knew exactly how the whole thing was put together.”

But when GHGSat began to scale, the company faced a decision, Germain said. “Do we triple or quadruple our [ground system technology] team here, and maybe start building our own antennas and having our own ground stations and leases and all those kinds of fun? Or do we just outsource all that?”

Opting for the outsourcing route, GHGSat’s experience as a mission owner made it an expert customer, Germain says, and a good partner.

“We know how to operate on satellites. We've done all the licensing, all the ground stuff. We understand all the conflicts, we understand how to manage all of them. So, when there are issues, we tend to be a pretty good partner for figuring out how to get to a win-win for [our ground segment provider] and for us.”

It's a very collegial, partnership oriented type of approach, as long as we've got good, expert people internally,” Germain concludes.

Beyond Partnership

That partnership model doesn’t go far enough for Pierre Bertrand, co-founder and CEO of Skynopy. While working in Paris for satellite-as-a-service provider Loft Orbital, Bertrand and his Skynopy cofounders noticed that ground was a pain point for space startups.

Loft allowed operators to outsource their entire supply chain, even including the satellite itself, but its customers still had to wrestle with the ground segment. “We saw how painful it was for new satellite operators to handle the connectivity of their mission. Of course, the ground is the connectivity,” Bertrand recalls.

Outsourcing in and of itself cannot provide simplicity. Even if an operator outsources the ground segment, “It still needs to plan which ground station is it going to use, which antenna is it going to use, both on its satellites and on the ground, and so on,” he says, a complex and difficult process.

Bertrand says Skynopy’s vision is a world where satellite operators can get connectivity for their satellites “as easily as you operate your phone. When you make a call, you don’t need to know or care which antenna it’s using, what frequency, whether it’s Wi-Fi or 5G. You just want the service and your data and communication to be delivered.”

Ground-segment-as-a-service is like cloud computing, Bertrand observes. It’s built for companies that want to scale but don’t know how far or how fast. A myriad of newcomers to the industry plan to launch 10, 20 up to 50 satellites, but have to start small first.

One downside of this, he says, is that “the market is balkanized, super spread out. You don’t have one player with hundreds or thousands of satellites. You have 100 of these players with a handful of satellites. That is a massive commercial development and sales challenge.”

The drivers of customer demand for the ground segment are bandwidth, but also “freshness,” he explains. Operators not only need to downlink more data; they want to be able to do so more frequently.

New Earth Observation technologies like hyperspectral resolution, and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) require more bandwidth. New use cases for that data require more frequent downlinks, notes Bertrand. “They want more data, always more data,” he says.

Bandwidth is about technology, but freshness requires geography.

To downlink data to its hungry terrestrial network, a satellite in Low- or Medium-Earth orbit (LEO or MEO) has to be able to “see” a ground station below it as it passes over. That tyranny of geography dictated a hybrid model for Skynopy, which in June closed a $17.6 million funding round.

“For the freshness of data, the key thing is you have to have a large, large network of ground stations,” he says. The company plans to open two of its own ground stations next year. In the meantime, by leasing antenna time, or land to build their own antennas, from existing ground station owners, Skynopy has put together a network of 20 ground stations in just under a year.

“We aim to get to hundreds," says Bertrand, “This is how we offer our customers the lowest data latency or revisit time possible.”

Even vertically integrated constellations with their own ground stations will need the flexibility provided by ground station-as-a-service, he says, to get surge capacity, ensure redundancy or monetize downtime.

Skynopy is in talks with Planet Labs, for example, Bertrand says. Planet, which operates two constellations of EO smallsats in LEO, owns and operates its own ground stations, but is talking to Skynopy about partnering with the startup.

Such partnerships with ground service providers offer “additional [ground segment] capacity to meet the needs of our growing customer base,” Mark Longanbach, Planet senior vice president, for Missions, says. “These partnerships ensure we can maintain efficiency, adapt to fluctuating data volumes, and support bespoke customer requirements or surge periods.”

Planet’s decision to build its own network of ground stations was taken early on, says Longanbach, driven primarily by operational considerations. “Operationally, owning our network allowed us to dictate the speed and frequency of data downlink, which is critical for our mission of near-daily Earth imaging. This direct control ensures we can rapidly collect, process, and deliver data, minimizing latency from capture to customer,” he says.

Owning its own ground stations has brought Planet competitive advantages, Longanbach says, like the company’s radio subsystem that enables large downlink data volumes, and a scheduling system that allocates ground station resources.

The demand for data is fueling a different kind of convergence on the ground as well, says Randall Barney, executive director of the World Teleport Association, a trade group that represents ground station operators. “More and more, we’re seeing dishes going up at data centers, while we see more teleports offering data center-type services.”

That convergence between data centers and teleports is being driven in part by the increasing integration of satellite communications into the global telecom system, says Barney. It’s made possible by the virtualization of proprietary hardware like modems and new standards designed to ensure interoperability of radio frequency equipment, like those promoted by the Digital Intermediate Frequency Interoperability Consortium, or DIFI.

The still-missing piece is workforce skills and training. The staff on site “need to have specialized RF [radio frequency] knowledge and the specialized IP [Internet Protocol] knowledge as well,” explains Barney.

New Frontiers for Ground

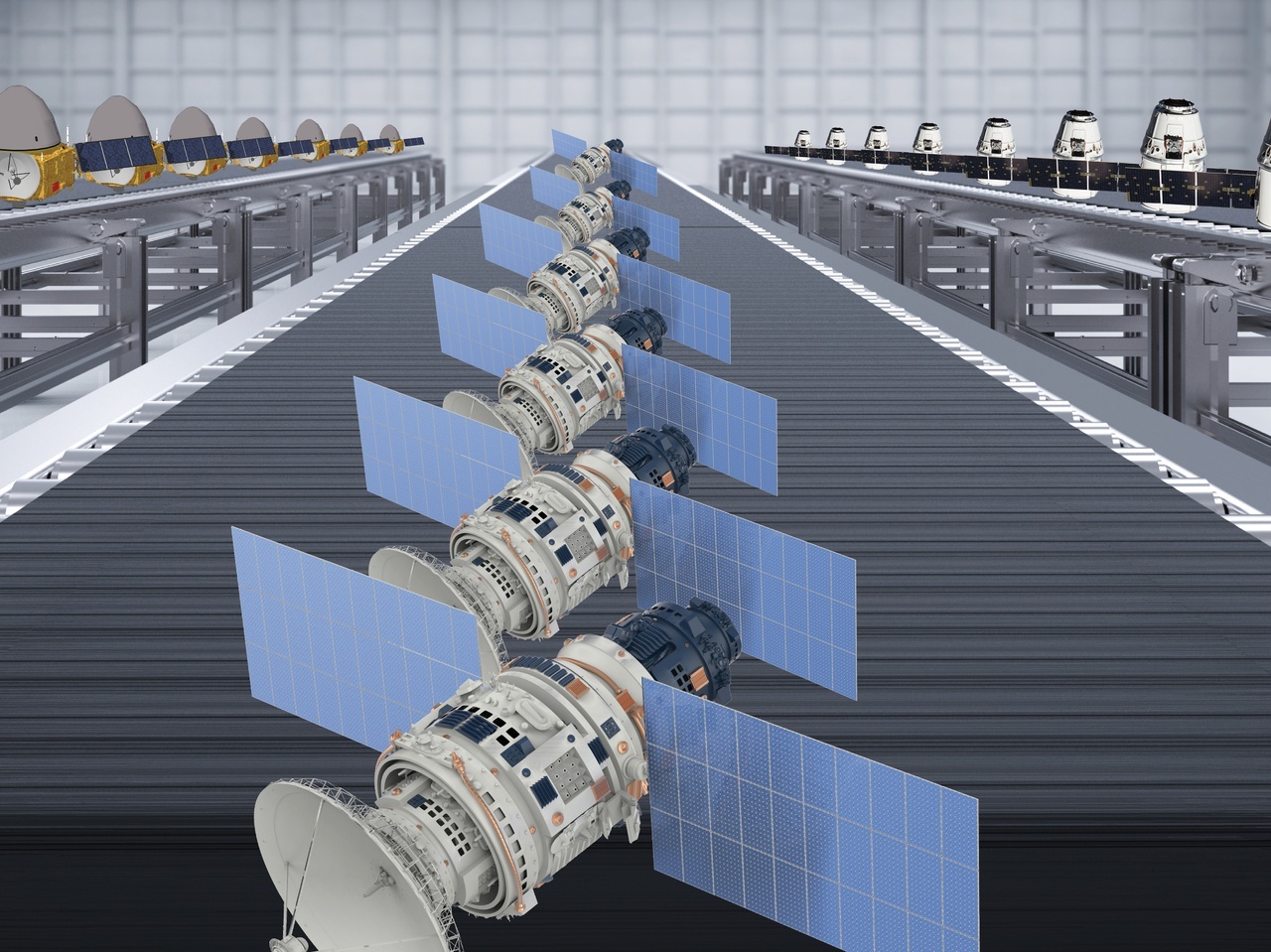

One trend impacting the ground market is that smallsats and larger satellites are converging, says Giovanni Pandolfi Bortoletto, co-founder and chief product officer of Leaf Space. The company, which has been in the ground-station-as-a-service business for more than a decade, cites itself as the second-largest player in that market now, measured by minutes of connectivity provided, right behind KSAT, the “OG” GSaaS provider.

Leaf Space’s network of 36 ground stations in 19 locations worldwide supports more than 120 satellites, from the smallest nanosats up to AST SpaceMobile’s Bluebird direct-to-phone communications satellites, which are the largest in LEO.

He estimates that up to a third of the satellites the company supports are over 500 kilograms.

Operators of large satellites are “coming to the smallsat world,” says Bortoletto, making their operations “more lean, more automated.” Smallsats, on the other hand, are growing in sophistication and data capacity. “I believe they are converging over time.”

But the more significant change in the market, he adds, is the growing demand for a high level of service. “A few years ago, the market was less demanding in service levels. Capacity was more important than the service level.”

That made it possible for some GSaaS providers to operate as brokers, aggregating different antennas under the same network, even though the antenna ownership was different. But with more customers now insisting on a higher level of service, GSaaS providers “need to have more control over the operational chain,” Bortoletto says. Leaf Space controls 100 percent of the time of the antennas that are on its network, he adds.

Additional control is provided by software, says Bortoletto. The company has an algorithm which optimizes antenna time distribution among customers based on their mission set. It also has an orchestration software layer that sits atop its ground stations.

This algorithm “enables us to run that infrastructure much more efficiently and abstract all the complexity away from the satellite operator,” he says. “We take care of moving the signals between their mission control center, to the right ground station which is, at that moment, in touch with their satellite, and then to uplink it, and the same in reverse with the data.”

Making an analogy to internet service, Bortoletto compares the brokered networks to “shared internet connectivity. It could be that it works well. It could be that it works less well.”

A wholly-owned ground network provider is like a dedicated fiber line, but the operator has to provide their own routing equipment. Leaf Space’s approach is like that of a standard ISP with a dedicated line, says Bortoletto, “So we try to give you the capacity that you need, abstracting all the complexity out of that.”

Both Leaf Space and Skynopy see on-orbit services, such as docking, refueling and space debris management as a future growth sector for ground station providers, the first wave of a new generation of in-orbit industries coming in future decades.

Although the number of satellites involved is much smaller than the LEO constellations for now, their need to maneuver requires always-on real-time data links, making them potentially profitable customers, explains Bortoletto.

Those high capacity, low latency data requirements “are great news for us,” agrees Skynopy’s Bertrand. VS

Shaun Waterman is an award-winning journalist and content strategist, writing about cybersecurity, space and emerging technology threats

Lead photo: A Leaf Space ground station